When people favor greater levels of income redistribution, we say their views are “liberal.” When people are pro-choice, we say their views are “liberal.” But does this mean that people who favor greater levels of income redistribution tend to be the same people as those who are pro-choice?

This has long been a source of tremendous confusion. It’s recently popped up in at least two places – Pew’s recent claim for the rise in consistently liberal and consistently conservative members of the public, and a new article on political ideology in Behavioral and Brain Sciences by Hibbing, Smith, and Alford.

I’ll cut to the chase: If one looks at data from the U.S. General Social Survey over the past 35 years on opinions on abortion and on government reduction of income differences, in fact the correlation is basically zero. Zilch. Nada. Nuthin. That is, there are as many people with ideologically mismatched views on these two issues as there are people with ideologically consistent views.

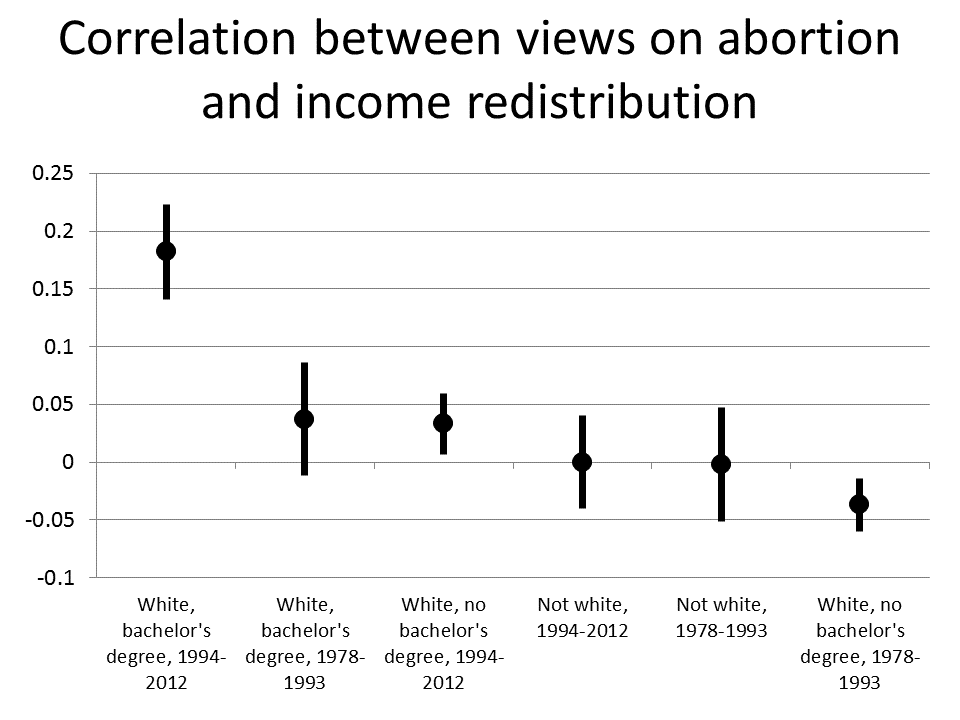

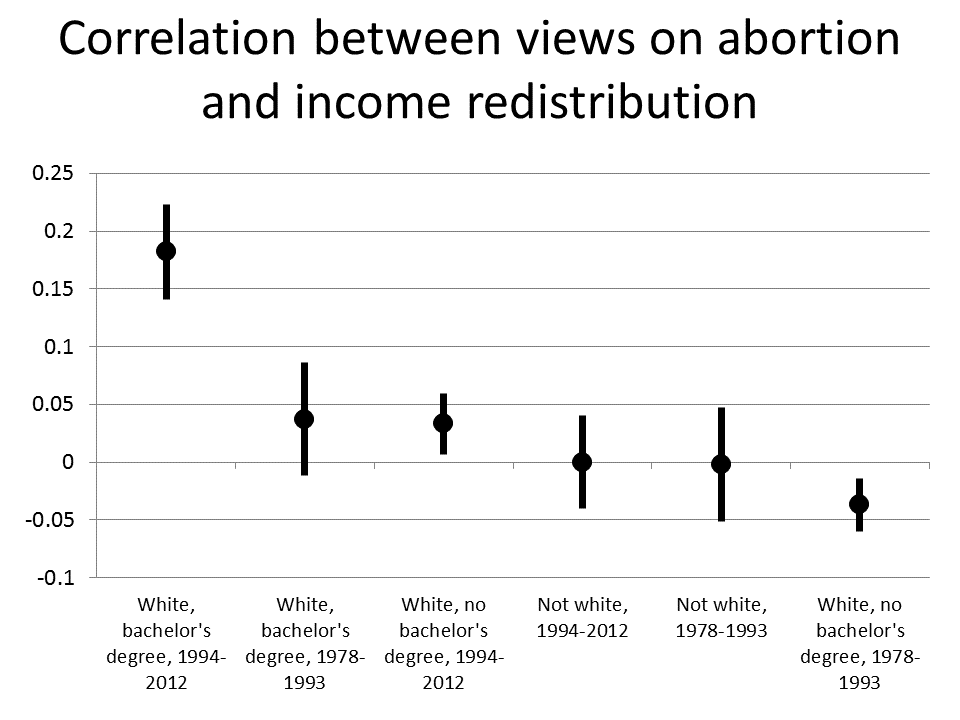

If one takes a deeper dive, it turns out that ideological coherence is higher recently, higher among whites, and higher among the well-educated. Put it all together and you get the numbers below, showing correlations (and the lines are 95% confidence intervals) for different demographic groups both in the earlier and later years of the sample.

In short, left-right coherence in the U.S. is a big deal only for college-educated whites, and then only really in recent years.

[Technical notes: For abortion, I standardized and averaged the GSS's main seven abortion items (ABDEFECT, etc.). For income redistribution, I standardized and averaged EQWLTH and GOVEQINC. In both cases, I used SPSS's "mean" command, which minimizes missing data. The resulting sample contained about 20,000 people. I split the sample into equal halves by year. "White" in this context means "non-Hispanic white," determined by combining the GSS's various race and ethnicity measures. The analyses are weighted combining the OVERSAMP and WTSSALL variables.]

Stop talking about how deep features of human nature produce “liberals” and “conservatives”

A lot of recent U.S. academic work on the nature of political issues involves online samples and samples of college students – in other words, mostly people who are college-educated whites. So, right, you look at those samples and you see higher levels of left-right coherence among different issue opinions (plus some libertarians).

But if you expand the view – look at past samples, look at non-college-educated samples, look at mostly non-white samples – the picture is very different. Here you’re about as likely to find off-axis people as left-right people.

What this means, of course, is that talk of how left-right clumping flows from “human nature” (or some related fundamental psychological something-or-other) uses a historically unusual and rather thin demographic slice to make claims about “humans” … in a situation where we actually already know that the generalization fails.

Stop saying that the main exception to the general liberal/conservative rule is libertarian

If one just looks at college-educated whites when it comes to abortion and income redistribution, in fact the largest group is “libertarian” – that is, people who are pro-choice but lean to the right on income redistribution. There are also plenty of “liberals” and “conservatives” as well. But there are very, very few people in the Region With No Agreed Name – people who are pro-life but on the left on income redistribution.

And so, researchers using online samples and college student samples often say, essentially: Most people skew “liberal” or “conservative” but there are a bunch of “libertarians” as well. (The Hibbing/Smith/Alford article I mentioned above does this, as does Jon Haidt’s recent work.)

However, look at African Americans in the general public and the biggest concentration lands in the Region With No Agreed Name, against abortion but in favor of income redistribution. In fact, there are about 3.5 times as many in that region as there are in the “libertarian” region. Among African Americans, there are almost as many in the nameless region as there are “liberals” and “conservatives” combined.

No, there’s nothing funny going on with views on abortion and income redistribution

Using GSS data limited to the 2000s, the abortion and income redistribution items both correlate substantially and roughly equally (.28 and .27, respectively) with whether people call themselves “liberal” vs. “conservative.” Looking at party identification, income redistribution has a nice correlation (.34) and abortion a smaller one (.20).

Hibbing/Smith/Alford have a discussion about how “economic issues are peripheral” in “political life” and about how “general attitudes towards taxes, social transfers, and big government” are “bloodless survey items” that “are not particularly meaningful.” It’s a bizarre set of comments given the kinds of well-known correlations I just mentioned.

Admit that we’re just not going to get off that easy

This stuff is complicated. Liberal-conservative coherence isn’t some natural necessity; it’s not even a routine feature of the modern public. We can’t just explain “liberals” and “conservatives” and be done with it. We’ve got to build up our explanations from the issues as they actually exist, with all their complicated, historically fluid, contingently coalitional, demographically related messiness.

Rob Kurzban and I try to make some progress in that direction in our new book (coming this Fall). In place of ideological clumping, we focus on something that seems to get lost in current academic discussions: These political issues aren’t just expressions of random perceptual biases or blind tribal affiliations; there’s a there there, a there that relates to the actual substance of the various issues. Public income redistribution helps people who are poorer and who lack private support (at the expense of richer people with richer social networks). The availability of family planning tools helps people who want to be sexually active while delaying having children (at the expense of people trying to minimize societal levels of casual sex). And some sexually-adventurous-but-child-delaying folks are, in fact, also richer people with richer social networks; and some casual-sex-minimizing-and-not-child-delaying folks are also poorer people with less private support. Perhaps the public’s complex, competing political positions have something to do with real life …